Operating System Notes

Introduction

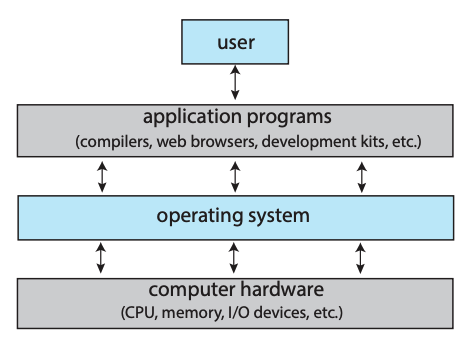

An operating system is a software that manages a computer’s hardware. It can

- control and manage the computer’s hardware and software

- organize and schedule the workload and resources distribution

- provide a convenient interface and environment for users and applications programs

The operating system has its own particularity, that is, its basic characteristics. The basic characteristics of an operating system include

- Concurrency - allow multitasking on the macro level by rapidly switching between processes on the micro level

- Sharing - allow resources to be shared by different processes

- Virtualization - abstract a computer’s hardware into several different execution environments.

- Asynchrony - the multitasking feature makes different process runs with unpredictable speed

In order to provide a good operating environment for multiprogramming, the operating system should have the following services:

- Process Management: A process is the fundamental unit of work in an operating system. Process management includes creating and deleting processes and providing mechanisms for processes to communicate and synchronize with each other.

- Memory Management: An operating system manages memory by keeping track of what parts of memory are being used and by whom. It is also responsible for dynamically allocating and freeing memory space.

- File Management: An operating system provides file systems for representing files and directories and managing space on mass-storage devices.

- I/O Management: An operating system controls the access of processes or users to the resources made available by the computer system.

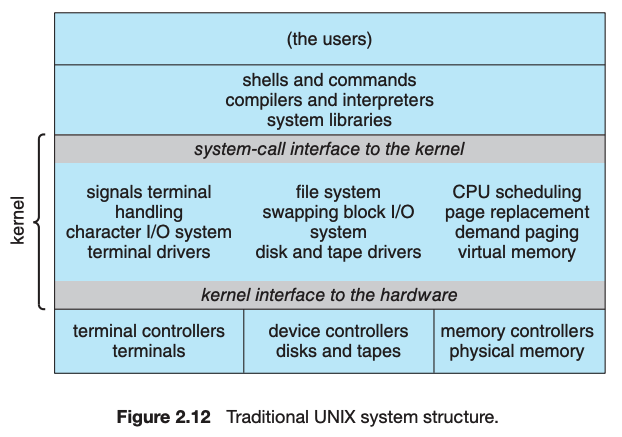

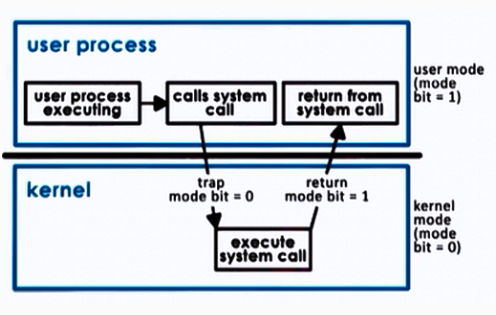

To prevent user programs from interfering with the proper operation of the system, the system hardware has two modes: user mode and kernel mode. Various instructions are privileged and can be executed only in kernel mode. Examples include the instruction to switch to kernel mode, I/O control, timer management, and interrupt management.

Interrupts are a key way in which hardware interacts with the operating system. A hardware device triggers an interrupt by sending a signal to the CPU to alert the CPU that some event requires attention. The interrupt is managed by the interrupt handler.

System calls provide an interface to the services made available by an operating system. Programmers use a system call’s application programming interface (API) for accessing system-call services. System calls can be divided into six major categories: (1) process control, (2) file management, (3) device management, (4) information maintenance, (5) communications, and (6) protection.

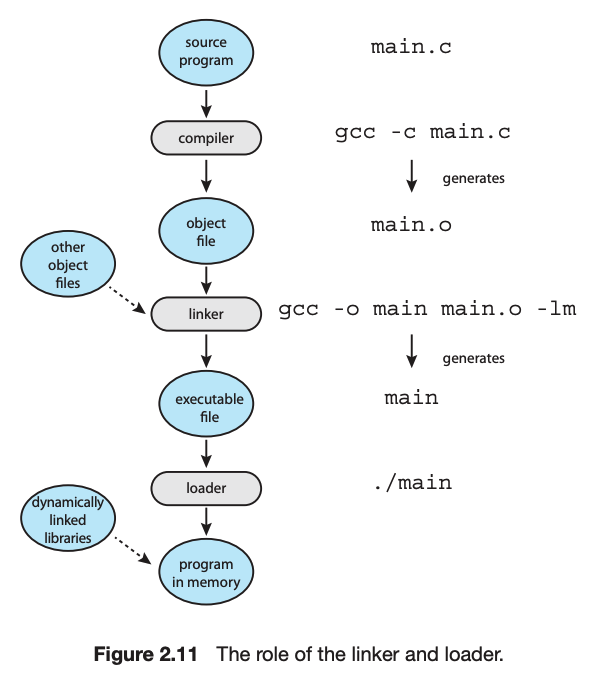

A linker combines several relocatable object modules into a single binary executable file. A loader loads the executable file into memory, where it becomes eligible to run on an available CPU.

Process Management

Process

A process is a program in execution, and the status of the current activity of a process is represented by the program counter, as well as other registers. The layout of a process in memory is represented by four different sections: (1) text, (2) data, (3) heap, and (4) stack. A process control block (PCB) is the kernel data structure that represents a process in an operating system. Notice that PCB is the only sign of the existence of the process!

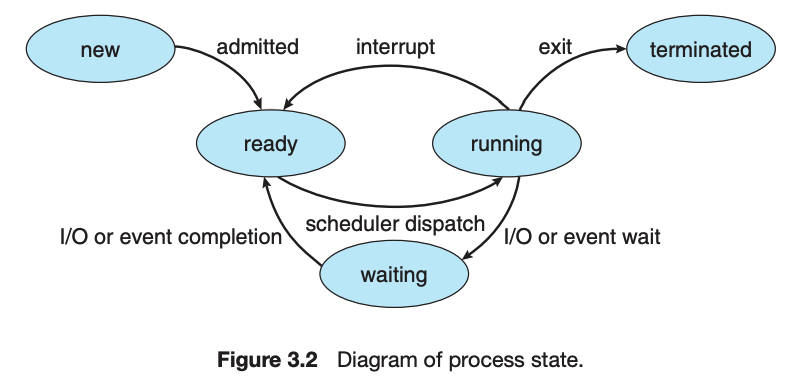

As a process executes, it changes state. There are four general states of a process: (1) ready, (2) running, (3) waiting, and (4) terminated.

An operating system performs a context switch when it switches from running one process to running another.

Interprocess communication refers to the exchange of information between processes. There are three main types of advanced communication methods:

- Sharing Memory: When shared memory is used for communication between processes, two (or more) processes share the same region of memory. POSIX provides an API for shared memory.

- Exchanging Message: Two processes may communicate by exchanging messages with one another using message passing. The Mach operating system uses message passing as its primary form of interprocess communication. Windows provides a form of message passing as well.

- Pipe Communication: A pipe provides a conduit for two processes to communicate. There are two forms of pipes, ordinary and named. Ordinary pipes are designed for communication between processes that have a parent–child relationship. Named pipes are more general and allow several processes to communicate.

Communication between processes in different computers

For Client–Server Systems, sockets and remote procedure calls (RPCs) are commonly used. Sockets allow two processes on different machines to communicate over a network. RPCs abstract the concept of function (procedure) calls in such a way that a function can be invoked on another process that may reside on a separate computer.

Thread

A thread represents a basic unit of CPU utilization, and threads belonging to the same process share many of the process resources, including code and data. There are four primary benefits to multithreaded applications: (1) responsiveness, (2) resource sharing.

Concurrency exists when multiple threads are making progress, whereas parallelism exists when multiple threads are making progress simultaneously. On a system with a single CPU, only concurrency is possible; parallelism requires a multicore system that provides multiple CPUs.

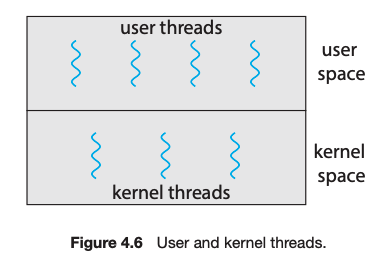

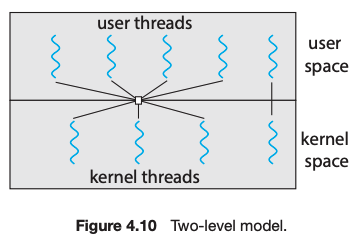

Thread implementation can be divided into two categories: user-level thread (ULT) and kernel-level thread (KLT). User applications create user-level threads, which must ultimately be mapped to kernel threads to execute on a CPU. The many-to-one model maps many user-level threads to one kernel thread. Other approaches include the one-to-one and many-to-many models.

A thread library provides an API for creating and managing threads. Three common thread libraries include Windows, Pthreads, and Java threading. Windows is for the Windows system only, while Pthreads is available for POSIX-compatible systems such as UNIX, Linux, and macOS. Java threads will run on any system that supports a Java virtual machine.

Threads may be terminated using either asynchronous or deferred cancellation. Asynchronous cancellation stops a thread immediately, even if it is in the middle of performing an update. Deferred cancellation informs a thread that it should terminate but allows the thread to terminate in an orderly fashion. In most circumstances, deferred cancellation is preferred to asynchronous termination.

Scheduling

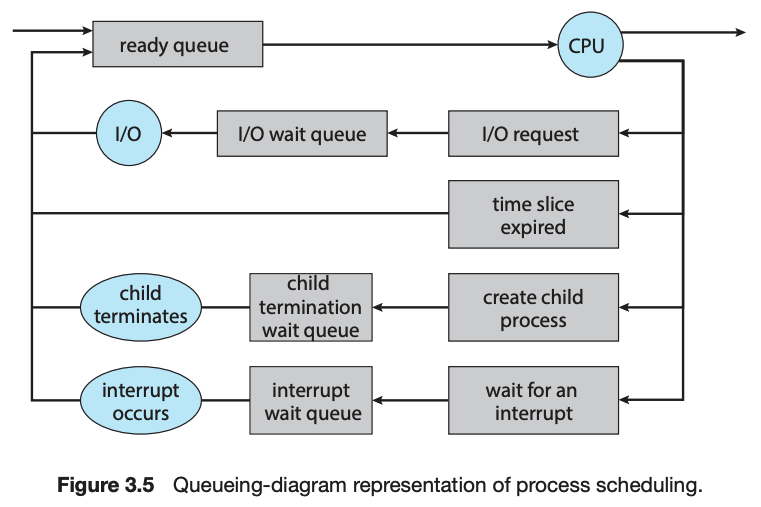

CPU scheduling is the task of selecting a waiting process from the ready queue and allocating the CPU to it. The CPU is allocated to the selected process by the dispatcher. Scheduling algorithms may be either preemptive (where the CPU can be taken away from a process) or nonpreemptive (where a process must voluntarily relinquish control of the CPU). Almost all modern operating systems are preemptive.

Scheduling algorithms can be evaluated according to the following five criteria: (1) CPU utilization, (2) throughput, (3) turnaround time, (4) waiting time, and (5) response time.

Common Scheduling Algorithms

- First-come, first-served (FCFS) scheduling is the simplest scheduling algorithm, but it can cause short processes to wait for very long processes.

- Shortest-job-first (SJF) scheduling is provably optimal, providing the shortest average waiting time. Implementing SJF scheduling is difficult, however, because predicting the length of the next CPU burst is difficult.

- Round-robin (RR) scheduling allocates the CPU to each process for a time quantum. If the process does not relinquish the CPU before its time quantum expires, the process is preempted, and another process is scheduled to run for a time quantum.

- Priority scheduling assigns each process a priority, and the CPU is allocated to the process with the highest priority. Processes with the same priority can be scheduled in FCFS order or using RR scheduling.

- Multilevel queue scheduling partitions processes into several separate queues arranged by priority, and the scheduler executes the processes in the highest-priority queue. Different scheduling algorithms may be used in each queue.

- Multilevel feedback queues are similar to multilevel queues, except that a process may migrate between different queues.

- Earliest-deadline-first (EDF) scheduling assigns priorities according to deadline. The earlier the deadline, the higher the priority; the later the deadline, the lower the priority.

Linux uses the completely fair scheduler (CFS), which assigns a proportion of CPU processing time to each task. The proportion is based on the virtual runtime (vruntime) value associated with each task. Windows scheduling uses a preemptive, 32-level priority scheme to determine the order of thread scheduling.

Some useful facts about Scheduling Algorithms:

- FCFS can cause long waiting times, especially when the first job takes too much CPU time.

- Both SJF and Shortest Remaining time first algorithms may cause starvation. Consider a situation when a long process is there in the ready queue and shorter processes keep coming.

- If time quantum for Round Robin scheduling is very large, then it behaves same as FCFS scheduling.

- SJF is optimal in terms of average waiting time for a given set of processes. SJF gives minimum average waiting time, but problems with SJF is how to know/predict the time of next job.

Synchronization and Dead Lock

A race condition occurs when processes have concurrent access to shared data and the final result depends on the particular order in which concurrent accesses occur. Race conditions can result in corrupted values of shared data.

A critical section is a section of code where shared data may be manipulated and a possible race condition may occur. The critical-section problem is to design a protocol whereby processes can synchronize their activity to cooperatively share data.

A solution to the critical-section problem must satisfy the following three requirements:

- Mutual exclusion: Mutual exclusion ensures that only one process at a time is active in its critical section.

- Progress: Progress ensures that programs will cooperatively determine what process will next enter its critical section.

- Bounded waiting: Bounded waiting limits how much time a program will wait before it can enter its critical section.

Software solutions to the critical-section problem, such as Peterson’s solution, do not work well on modern computer architectures.

Hardware support for the critical-section problem includes memory barriers; hardware instructions, such as the compare-and-swap instruction; and atomic variables.

A mutex lock provides mutual exclusion by requiring that a process acquire a lock before entering a critical section and release the lock on exiting the critical section.

Semaphores, like mutex locks, can be used to provide mutual exclusion. However, whereas a mutex lock has a binary value that indicates if the lock is available or not, a semaphore has an integer value and can therefore be used to solve a variety of synchronization problems.

A monitor is an abstract data type that provides a high-level form of process synchronization. A monitor uses condition variables that allow processes to wait for certain conditions to become true and to signal one another when conditions have been set to true.

Classic problems of process synchronization include the bounded-buffer, readers–writers, and dining-philosophers problems.

Deadlock occurs in a set of processes when every process in the set is waiting for an event that can only be caused by another process in the set. Deadlock can arise if following four conditions hold simultaneously (Necessary Conditions):

- Mutual Exclusion – One or more than one resource are non-sharable (Only one process can use at a time).

- Hold and Wait – A process is holding at least one resource and waiting for resources.

- No Preemption – A resource cannot be taken from a process unless the process releases the resource.

- Circular Wait – A set of processes are waiting for each other in circular form.

Deadlocks can be prevented by ensuring that one of the four necessary conditions for deadlock cannot occur. There are three ways to handle deadlock:

- Deadlock prevention: The idea is to set certain limitation to avoid one or more conditions that caused the deadlock.

- Deadlock avoidance: The idea is to use certain method to let the system into deadlock state when allocating the resources.

- Deadlock detection and recovery : Let deadlock occur, use certain algorithm to evaluate processes and resources on a running system to determine if a set of processes is in a deadlocked state. If deadlock does occur, a system can attempt to recover from the deadlock by either aborting one of the processes in the circular wait or preempting resources that have been assigned to a deadlocked process.

Deadlock can be avoided by using the banker’s algorithm, which does not grant resources if doing so would lead the system into an unsafe state where deadlock would be possible.

Memory Management

Main Memory

Memory is central to the operation of a modern computer system and consists of a large array of bytes, each with its own address. One way to allocate an address space to each process is through the use of base and limit registers. The base register holds the smallest legal physical memory address, and the limit specifies the size of the range.

Binding symbolic address references to actual physical addresses may occur during (1) compile, (2) load, or (3) execution time.

An address generated by the CPU is known as a logical address, which the memory management unit (MMU) translates to a physical address in memory.

These techniques allow the memory to be shared among multiple processes:

- Overlays – The memory should contain only those instructions and data that are required at a given time.

- Swapping – In multiprogramming, the instructions that have used the time slice are swapped out from the memory.

Contiguous Memory Allocation

- Single Partition Allocation Schemes – The memory is divided into two parts. One part is kept to be used by the OS and the other is kept to be used by the users.

- Fixed Partition – The memory is divided into fixed size partitions.

- Variable Partition – The memory is divided into variable sized partitions.

- First Fit – The arriving process is allotted the first hole of memory in which it fits completely.

- Best Fit – The arriving process is allotted the hole of memory in which it fits the best by leaving the minimum memory empty.

- Worst Fit – The arriving process is allotted the hole of memory in which it leaves the maximum gap.

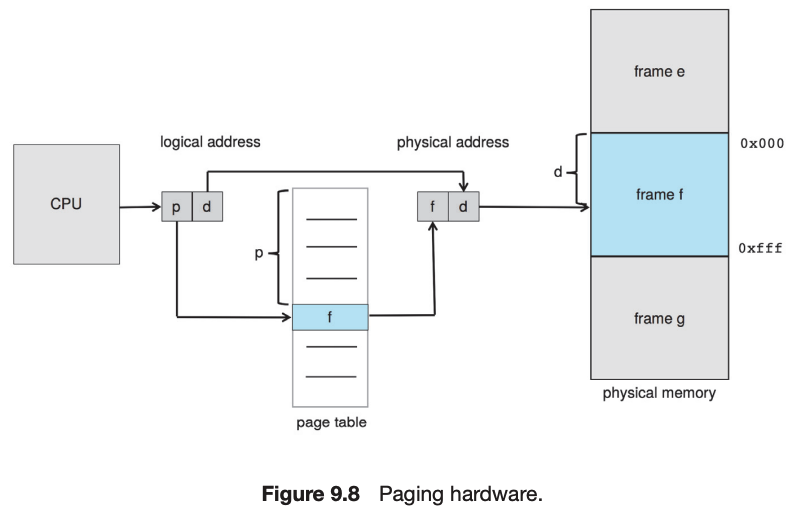

Modern operating systems use paging to manage memory. In this process, physical memory is divided into fixed-sized blocks called frames and logical memory into blocks of the same size called pages. When paging is used, a logical address is divided into two parts: a page number and a page offset. The page number serves as an index into a per-process page table that contains the frame in physical memory that holds the page. The offset is the specific location in the frame being referenced.

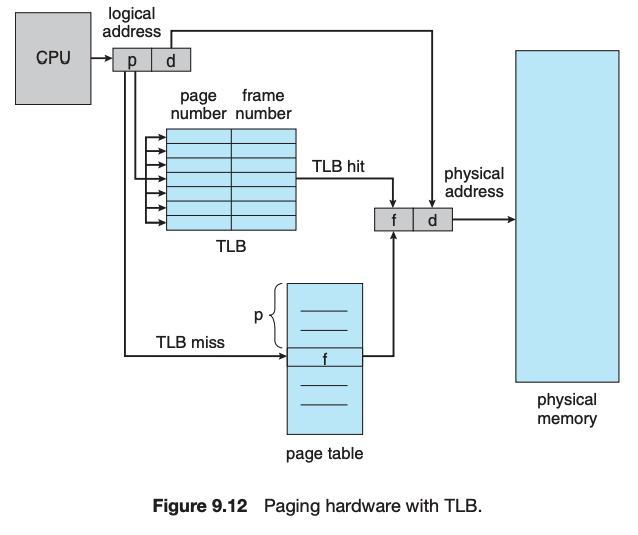

A translation look-aside buffer (TLB) is a hardware cache of the page table. Each TLB entry contains a page number and its corresponding frame. Using a TLB in address translation for paging systems involves obtaining the page number from the logical address and checking if the frame for the page is in the TLB. If it is, the frame is obtained from the TLB. If the frame is not present in the TLB, it must be retrieved from the page table.

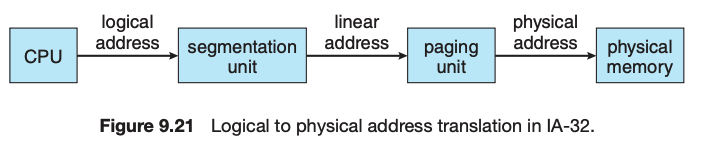

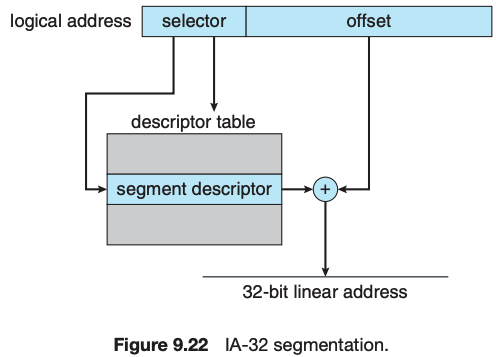

Segmentation is implemented to give users view of memory. The logical address space is a collection of segments. Segmentation can be implemented with or without the use of paging. The CPU generates logical addresses, which are given to the segmentation unit. The segmentation unit produces a linear address for each logical address. The linear address is then given to the paging unit, which in turn generates the physical address in main memory.

Virtual Memory

Virtual memory abstracts physical memory into an extremely large uniform array of storage. The benefits of virtual memory include the following:

- a program can be larger than physical memory;

- a program does not need to be entirely in memory;

- processes can share memory;

- processes can be created more efficiently.

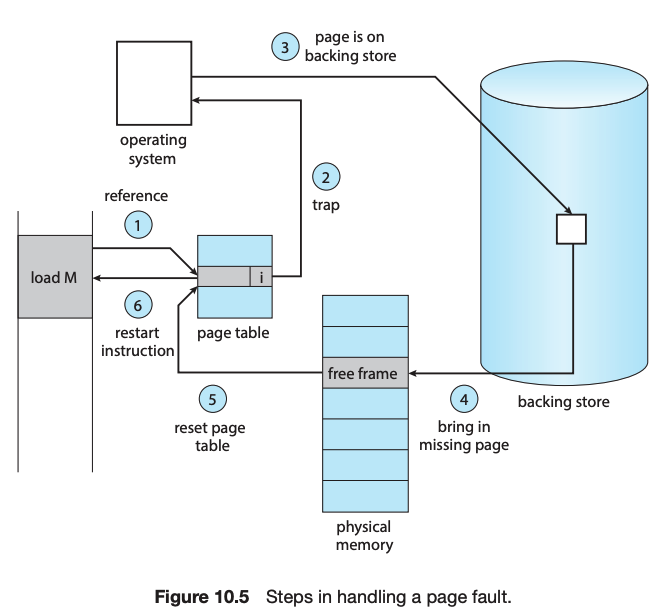

Demand paging is a technique whereby pages are loaded only when they are demanded during program execution. Pages that are never demanded are thus never loaded into memory. A page fault occurs when a page that is currently not in memory is accessed. The page must be brought from the backing store into an available page frame in memory.

When available memory runs low, a page-replacement algorithm selects an existing page in memory to replace with a new page. Page-replacement algorithms include FIFO, optimal, and LRU. Pure LRU algorithms are impractical to implement, and most systems instead use LRU-approximation algorithms.

-

First In First Out (FIFO)

This is the simplest page replacement algorithm. In this algorithm, operating system keeps track of all pages in the memory in a queue, oldest page is in the front of the queue. When a page needs to be replaced page in the front of the queue is selected for removal. For example, consider page reference string 1, 3, 0, 3, 5, 6 and 3 page slots. Initially, all slots are empty, so when 1, 3, 0 came they are allocated to the empty slots —> 3 Page Faults. When 3 comes, it is already in memory so —> 0 Page Faults. Then 5 comes, it is not available in memory so it replaces the oldest page slot i.e 1. —> 1 Page Fault. Finally, 6 comes, it is also not available in memory so it replaces the oldest page slot i.e 3 —> 1 Page Fault.

Belady’s anomaly:

Belady’s anomaly proves that it is possible to have more page faults when increasing the number of page frames while using the First in First Out (FIFO) page replacement algorithm. For example, if we consider reference string 3 2 1 0 3 2 4 3 2 1 0 4 and 3 slots, we get 9 total page faults, but if we increase slots to 4, we get 10 page faults.

-

Optimal Page replacement In this algorithm, pages are replaced which are not used for the longest duration of time in the future. Let us consider page reference string 7 0 1 2 0 3 0 4 2 3 0 3 2 and 4 page slots. Initially, all slots are empty, so when 7 0 1 2 are allocated to the empty slots —> 4 Page faults. 0 is already there so —> 0 Page fault. When 3 came it will take the place of 7 because it is not used for the longest duration of time in the future.—> 1 Page fault. 0 is already there so —> 0 Page fault. 4 will takes place of 1 —> 1 Page Fault. Now for the further page reference string —> 0 Page fault because they are already available in the memory.

Optimal page replacement is perfect, but not possible in practice as an operating system cannot know future requests. The use of Optimal Page replacement is to set up a benchmark so that other replacement algorithms can be analyzed against it.

-

Least Recently Used (LRU) In this algorithm, the page will be replaced which is least recently used. Let say the page reference string 7 0 1 2 0 3 0 4 2 3 0 3 2 . Initially, we have 4-page slots empty. Initially, all slots are empty, so when 7 0 1 2 are allocated to the empty slots —> 4 Page faults. 0 is already their so —> 0 Page fault. When 3 came it will take the place of 7 because it is least recently used —> 1 Page fault. 0 is already in memory so —> 0 Page fault. 4 will takes place of 1 —> 1 Page Fault. Now for the further page reference string —> 0 Page fault because they are already available in the memory.

Thrashing occurs when a system spends more time paging than executing.

A locality represents a set of pages that are actively used together. As a process executes, it moves from locality to locality. A working set is based on locality and is defined as the set of pages currently in use by a process.

Linux, Windows, and Solaris manage virtual memory similarly, using demand paging and copy-on-write, among other features. Each system also uses a variation of LRU approximation known as the clock algorithm.

File Management

A file is an abstract data type defined and implemented by the operating system. It is a sequence of logical records. A logical record may be a byte, a line (of fixed or variable length), or a more complex data item. The operating system may specifically support various record types or may leave that support to the application program.

File System

Collection of files is a file directory. The directory contains information about the files, including attributes, location and ownership. Much of this information, especially that is concerned with storage, is managed by the operating system.

- A single-level directory in a multiuser system causes naming problems, since each file must have a unique name.

- A two-level directory solves this problem by creating a separate directory for each user’s files. The directory lists the files by name and includes the file’s location on the disk, length, type, owner, time of creation, time of last use, and so on.

- A tree-structured directory allows a user to create subdirectories to organize files. Acyclic-graph directory structures enable users to share subdirectories and files but complicate searching and deletion. A general graph structure allows complete flexibility in the sharing of files and directories but sometimes requires garbage collection to recover unused disk space.

Since files are the main information-storage mechanism in most computer systems, file protection is needed on multiuser systems. Access to files can be controlled separately for each type of access — read, write, open, close, execute, append, create, delete, list directory, and so on. File protection can be provided by access lists, passwords, or other techniques。

File systems are often implemented in a layered or modular structure. The lower levels deal with the physical properties of storage devices and communicating with them. Upper levels deal with symbolic file names and logical properties of files.

The various files within a file system can be allocated space on the storage device in three ways: through contiguous, linked, or indexed allocation.

- Continuous Allocation: A single continuous set of blocks is allocated to a file at the time of file creation. Contiguous allocation can suffer from external fragmentation and also makes it hard to extend a file.

- Linked Allocation: Allocation is on an individual block basis. Each block contains a pointer to the next block in the chain. Direct access is very inefficient with linked allocation.

- Indexed Allocation: It addresses many of the problems of contiguous and chained allocation. In this case, the file allocation table contains a separate one-level index for each file. Indexed allocation may require substantial overhead for its index block.

These algorithms can be optimized in many ways. Contiguous space can be enlarged through extents to increase flexibility and to decrease external fragmentation. Indexed allocation can be done in clusters of multiple blocks to increase throughput and to reduce the number of index entries needed. Indexing in large clusters is similar to contiguous allocation with extents.

Free-space allocation methods also influence the efficiency of disk-space use, the performance of the file system, and the reliability of secondary storage. The methods used include bit vectors and linked lists. Optimizations include grouping, counting, and the FAT (File Allocation Table), which places the linked list in one contiguous area.

Most systems are multi-user and thus must provide a method for file sharing and file protection. Frequently, files and directories include metadata, such as owner, user, and group access permissions.

Disk Management

Hard disk drives and nonvolatile memory devices are the major secondary storage I/O units on most computers. Modern secondary storage is structured as large one-dimensional arrays of logical blocks. Drives of either type may be attached to a computer system in one of three ways: (1) through the local I/O ports on the host computer, (2) directly connected to motherboards, or (3) through a communications network or storage network connection.

Disk-scheduling algorithms can improve the effective bandwidth of HDDs, the average response time, and the variance in response time. Algorithms such as SCAN and C-SCAN are designed to make such improvements through strategies for disk-queue ordering. Performance of disk-scheduling algorithms can vary greatly on hard disks. In contrast, because solid-state disks have no moving parts, performance varies little among scheduling algorithms, and quite often a simple FCFS strategy is used.

Disk Scheduling Algorithms:

- FCFS: FCFS is the simplest of all the Disk Scheduling Algorithms. In FCFS, the requests are addressed in the order they arrive in the disk queue.

- SSTF: In SSTF (Shortest Seek Time First), requests having shortest seek time are executed first. So, the seek time of every request is calculated in advance in a queue and then they are scheduled according to their calculated seek time. As a result, the request near the disk arm will get executed first.

- SCAN: In SCAN algorithm the disk arm moves into a particular direction and services the requests coming in its path and after reaching the end of the disk, it reverses its direction and again services the request arriving in its path. So, this algorithm works like an elevator and hence also known as elevator algorithm.

- CSCAN: In SCAN algorithm, the disk arm again scans the path that has been scanned, after reversing its direction. So, it may be possible that too many requests are waiting at the other end or there may be zero or few requests pending at the scanned area.

- LOOK: It is similar to the SCAN disk scheduling algorithm except for the difference that the disk arm in spite of going to the end of the disk goes only to the last request to be serviced in front of the head and then reverses its direction from there only. Thus it prevents the extra delay which occurred due to unnecessary traversal to the end of the disk.

- C-LOOK: As LOOK is similar to SCAN algorithm, in a similar way, CLOOK is similar to CSCAN disk scheduling algorithm. In CLOOK, the disk arm in spite of going to the end goes only to the last request to be serviced in front of the head and then from there goes to the other end’s last request. Thus, it also prevents the extra delay which occurred due to unnecessary traversal to the end of the disk.

Data storage and transmission are complex and frequently result in errors. Error detection attempts to spot such problems to alert the system for corrective action and to avoid error propagation. Error correction can detect and repair problems, depending on the amount of correction data available and the amount of data that was corrupted.

I/O Management

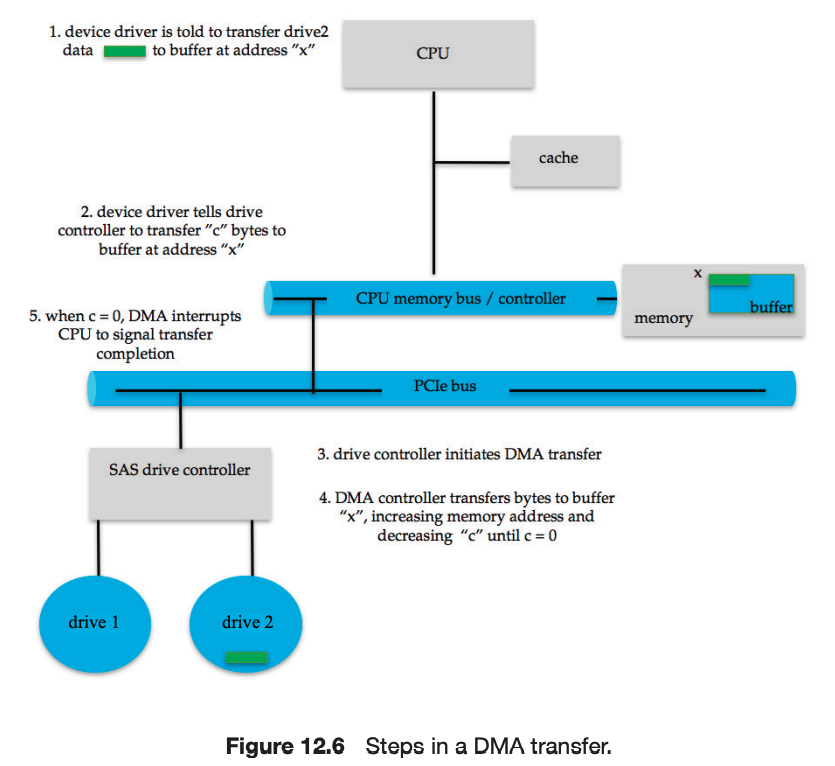

The basic hardware elements involved in I/O are buses, device controllers, and the devices themselves. The work of moving data between devices and main memory is performed by the CPU as programmed I/O or is offloaded to a DMA controller.

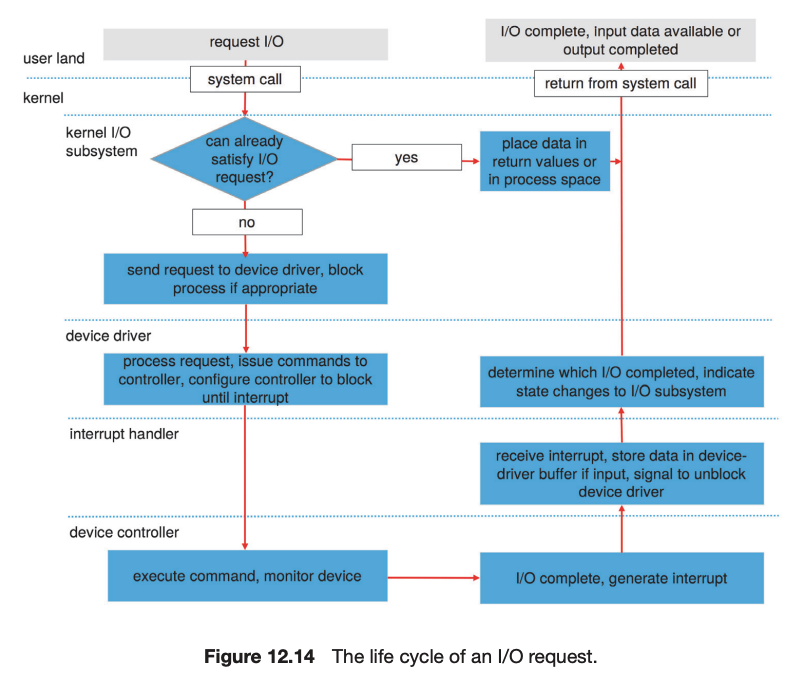

The kernel module that controls a device is a device driver. The system-call interface provided to applications is designed to handle several basic categories of hardware, including block devices, character-stream devices, memory-mapped files, network sockets, and programmed interval timers. The system calls usually block the processes that issue them, but non-blocking and asynchronous calls are used by the kernel itself and by applications that must not sleep while waiting for an I/O operation to complete.

The kernel’s I/O subsystem provides numerous services. Among these are I/O scheduling, buffering, caching, spooling, device reservation, error handling. Another service, name translation, makes the connections between hardware devices and the symbolic file names used by applications. It involves several levels of mapping that translate from character-string names, to specific device drivers and device addresses, and then to physical addresses of I/O ports or bus controllers. This mapping may occur within the file-system name space, as it does in UNIX, or in a separate device name space, as it does in MS-DOS.

I/O system calls are costly in terms of CPU consumption because of the many layers of software between a physical device and an application. These layers imply overhead from several sources: context switching to cross the kernel’s protection boundary, signal and interrupt handling to service the I/O devices, and the load on the CPU and memory system to copy data between kernel buffers and application space.